Underwriting Multifamily Loss-to-Lease

When I started my commercial real estate career, one of the most challenging concepts to wrap my head around was loss-to-lease (or LTL). It always felt like an unnecessary accounting item that mucked up the income statements and made multifamily financial analysis much more challenging than it should have been.

Loss-to-Lease Article Focus

What is Loss-to-Lease?

In theory, the concept is simple. The loss-to-lease calculation is:

Loss-to-lease = Market Rents - Leased Rents

If leased rents exceed market rents, you can have “gain”-to-lease. The problem I encountered frequently was that everybody uses different terminology for "rent." Examples include:

Market Rates

Actual Rent Rates

In-Place Leased Rent

Gross Potential Rent

Rental Income

Effective Rent

Often, it felt like a wild goose chase getting to the crux of a supposedly simple question: What are the current rent levels at the property?

Rental Terminology Definitions

Before diving deeper into loss-lease and how it can affect proforma analysis, I'll go over some common terminology and what it means.

Market Rents

This is the threshold a property could or potentially should be rented for. In my opinion, the market rent is subjective. It could be a property manager pegging a rental amount to the units dependent on the comps in the submarket. For example, if the 1-BR unit next door is rented for $1,100 with inferior finish levels to our property, we could set the market rent for our 1-BR to $1,200. It's our estimate of what the unit is worth to a new tenant/future move-in. The final lease could be signed for any amount, but setting up a "baseline" rental target can be a good course of action to judge your leasing performance.

Market rents can also be determined by leasing software. Managers will frequently depend on multifamily leasing software to determine lease rates at a property. Ownership will be responsible for plugging in all the amenities rental units possess and the communal amenities.

Multifamily leasing software programs can "price" these amenities and benchmark them with comps in the marketplace to develop achievable market rents that constantly fluctuate as market factors change. Sophisticated ownership groups will incorporate algorithm-based software to push property management to achieve higher rents.

In summary, the market rent is just a budgeted rent. It can be calculated with algorithms, rent comp surveys, or simply from a gut feeling of a property owner.

Actual Rents

The actual rents at the property are where my analysis begins. The definition is simple:

What is the amount for which they signed the actual lease?

All rental leases should be included in the rent roll.

Synonymous terminology will include:

Lease Rents

In-Place Rents

In-Pace Leased Rents

Market rents tell you a story—What should/could rent be at the property? Actual Rents are what tenants signed the lease for. This is where my proforma analysis will begin. I will largely ignore market rents and start projecting proforma rents from actual rents. I only care about the actual leases. I will then research the property and submarket to determine bankable market rents and underwrite accordingly.

Note: If there are vacant units, I will assume their actual rent is the average of occupied units of the same floor plan.

For example, if three studio units with a square footage 650 have an average rent of $900, I will project that rent to the vacant 650 square-foot studio unit.

When Market Rents > Actual Rents, the property exhibits loss to lease. If, on average, the market rent is $1,300 while the actual rent is $1,150 for a 100-unit property, the loss to lease for that month is $15,000.

Market Rent: $1,300 x 100 units = $130,000

Actual Rent: $1,150 x 100 unit = $115,000

Loss-to-Lease = $15,000

The vast majority of properties that track a market rent will experience loss-to-lease. However, you will encounter instances where Actual Rents > Market Rents and the property exhibits a “gain-to-lease.”

Effective Rents

The final definition is for effective rents. Effective rents are:

Effective Rents = Actual Rents - Concessions

If a property is renting a 2BR unit for $1,500 but is giving the resident a month free if they sign a 12-month lease term, the effective rent lease calculation is:

$1,500 x 12 = $18,000

$18,000 - $1,500 (1 free month) = $16,500

Effective Monthly Rent = $16,500 / 12 = $1,375

If a property is giving away concessions, they usually allocate them in two ways:

Upfront

Over the lease term

Upfront

An upfront concession is the most common. If the concession is one month free, the tenants' first month of rent will be $0. The owner will take a one-time loss on the unit, but the tenant will pay full rent for the remainder of the lease term.

Over Lease Term

The other way is to allocate the concession over the lease term. Using the same example above with the $1,500 actual rent and 1-month concession, the two concession methods on a 12-month lease would look like this:

Upfront: 1st month = $0, remaining 11 months = $1,500/month

Over Lease Term: All 12 months = $1,375

While the following effect on cash flow over 12 months is identical, allocating concessions over the lease term is disadvantageous for two reasons.

Renter Psychology - Increasing the $1,500 rental rate to $1,550 will be hard to stomach for the renter paying $1,375 for the year. The renter who received one free month 11 months ago will be used to pay $1,500 by the time the renewal notice comes out. Stomaching a $50 increase is much less of a shock than $175.

Sales Effort - If you sell your property with leases with concessions baked into the rents, the next ownership group will inherit this concession loss (for the remainder of any lease term with recurring concessions). This may hurt their potential income upside as their Year 1 net operating income (NOI) would be less in their proforma, leading to a lower cap rate that could affect the property value. If the renters pay the concession upfront, you’d take 100% of the loss, but the next ownership group would have a clean slate to project rents as they please.

Proforma Loss-to-Lease

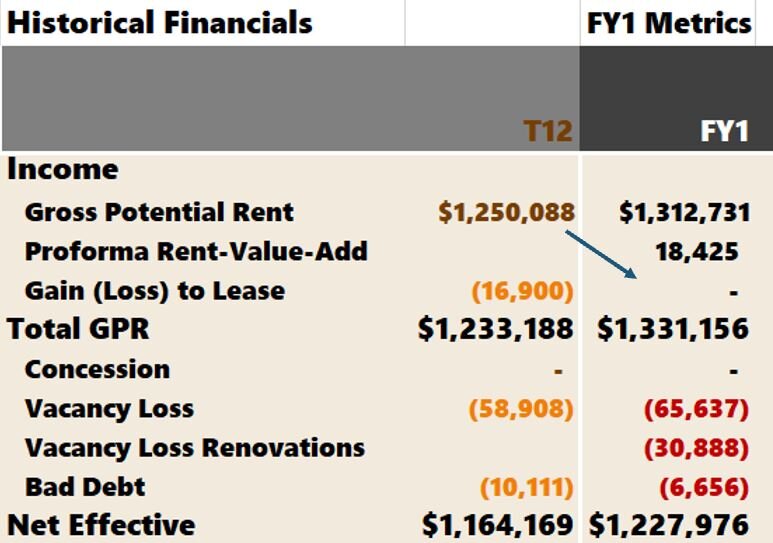

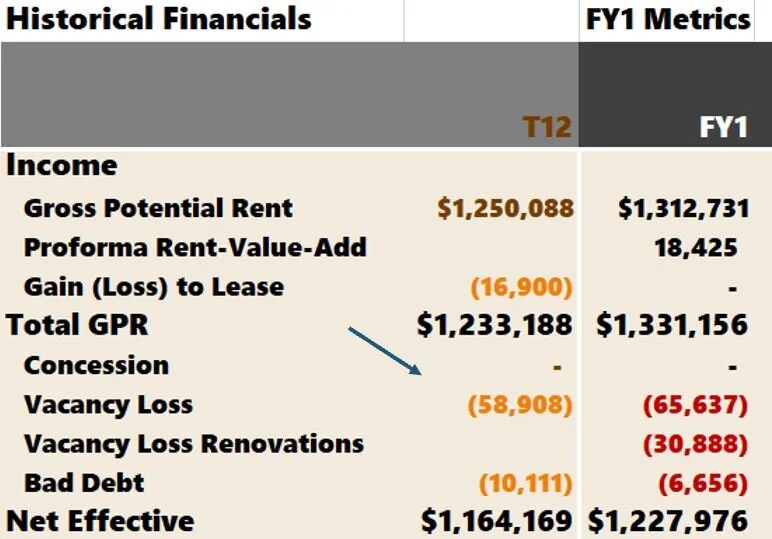

While the Tactica value-add model includes a loss-to-lease line item, it is never something I will account for once the proforma begins. If the historical financials show a loss-to-lease, I will plug this into the historical analysis when I input T3 and T12 historical data.

However, I collect only actual rents from the Excel rent roll. I will project rent growth from these in-place actual rents.

Therefore, in the proforma, Gross Potential Rent (GPR) = Actual Rents in the rent roll x 12 (to annualize). The loss-to-lease line item in Year 1 of the proforma will be $0.

Depending on the investment strategy (value-add, core plus, etc.), I will apply an appropriate growth rate to the actual rents. You'll notice I have a separate line item dedicated to concessions.

I like to underwrite concessions separately from the actual rents. The only caveat is if ownership bakes concessions into the leased rents (which is inferior and rare, in my opinion). Then, I will start the proforma with "Effective Rents." My GPR Year 1 would be the effective rents of the property, and both loss-to-lease and concession line items would be $0.

Beware of Loss-to-Lease Cutting

Often, you will come across proforma underwriting that includes market rents, loss to lease, and concessions as three separate line items. You'll see underwriting that:

Increases the market rent by "x" %

Decreases the loss-to-lease by "x" %

Decreases the concessions by "x" %

I get annoyed when underwriting is presented his way, as it makes the overall rental picture murky. It's not necessarily incorrect to do it this way; it just takes extra steps to determine the most critical question:

What are the projected rent levels at the property?

Increasing market rents and decreasing loss-to-lease and concessions modestly can have huge gains on effective rental increases and potentially inflate a realistic, effective gross income (EGI) target of a multifamily property.

For example, if I increase market rents by 3% but cut loss-to-lease and concessions by 20% each, total effective rents can increase significantly (depending on concessions and LTL levels). That may be tough to achieve in one year. If you start with the actual rents, you get to the brass tacks right from the get-go.

Summarizing Loss-to-Lease

Loss-to-Lease/Gain-to-Lease is how much actual rents deviated from budgeted market rents. During proforma underwriting, it can skew the proper rent data and make it more challenging to assess the true rent levels at the property.

I've found it worthwhile to largely ignore the market rents of a given property, seek out the actual rents, and begin my proforma underwriting using the actual rents as the baseline. This is more transparent, involves fewer steps, and, in my opinion, facilitates better communications between buying and selling parties when discussing the proforma projections.